Welcome to educatin.site. Today, we’re exploring a quiet revolution happening on the factory floor: flexible manufacturing. This modern approach demands production systems that can switch quickly between making different products.

The key enabler for this adaptability is emerging technology, specifically soft robotic actuators. These devices are radically changing how automation handles product variety, moving beyond the rigid, clunky machines of the past.

Understanding Flexible Manufacturing

Traditional manufacturing lines are often set up to produce one product efficiently, like a specific model of car or phone. Changing that line to make a new product is a lengthy and expensive process called retooling.

Flexible manufacturing, by contrast, is designed for rapid adjustment. Think of a single line producing both small, delicate electronics and larger, robust components within the same hour.

This requires machinery that can dynamically change its grip, force, and movement. It’s all about minimizing downtime and maximizing the ability to handle a variable product portfolio.

Why Flexibility is Essential

Consumer demands are constantly shifting, leading to shorter product life cycles and more customization. Companies must react quickly to these changes or risk falling behind.

A flexible system allows a manufacturer to produce smaller batches of diverse products economically. This capability minimizes waste, reduces storage costs, and keeps inventory fresh and relevant.

It moves the focus from sheer volume to agile response, ensuring the production process supports modern market dynamics.

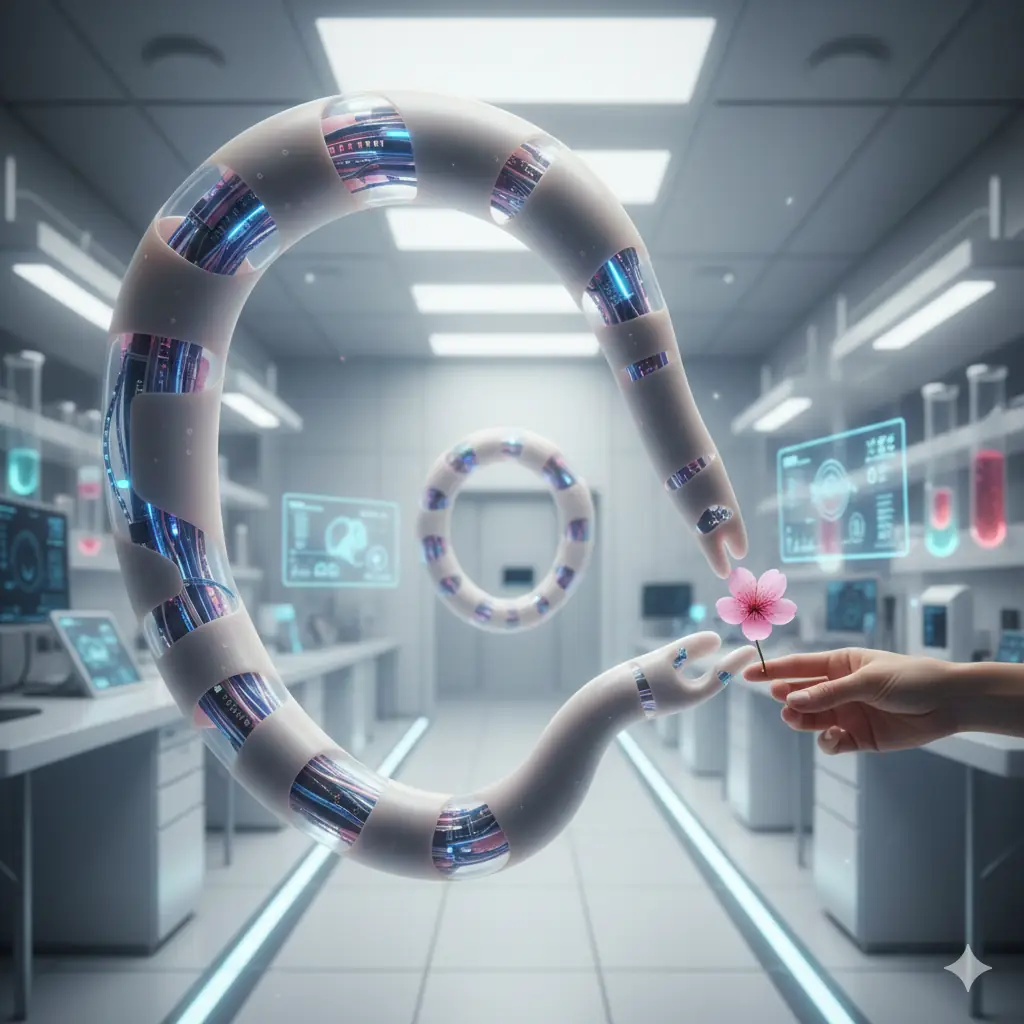

Introducing Soft Robotic Actuators

An actuator is essentially the ‘muscle’ of a robot, converting energy into motion. Historically, these have been rigid motors, pistons, and gearboxes made of hard materials like metal.

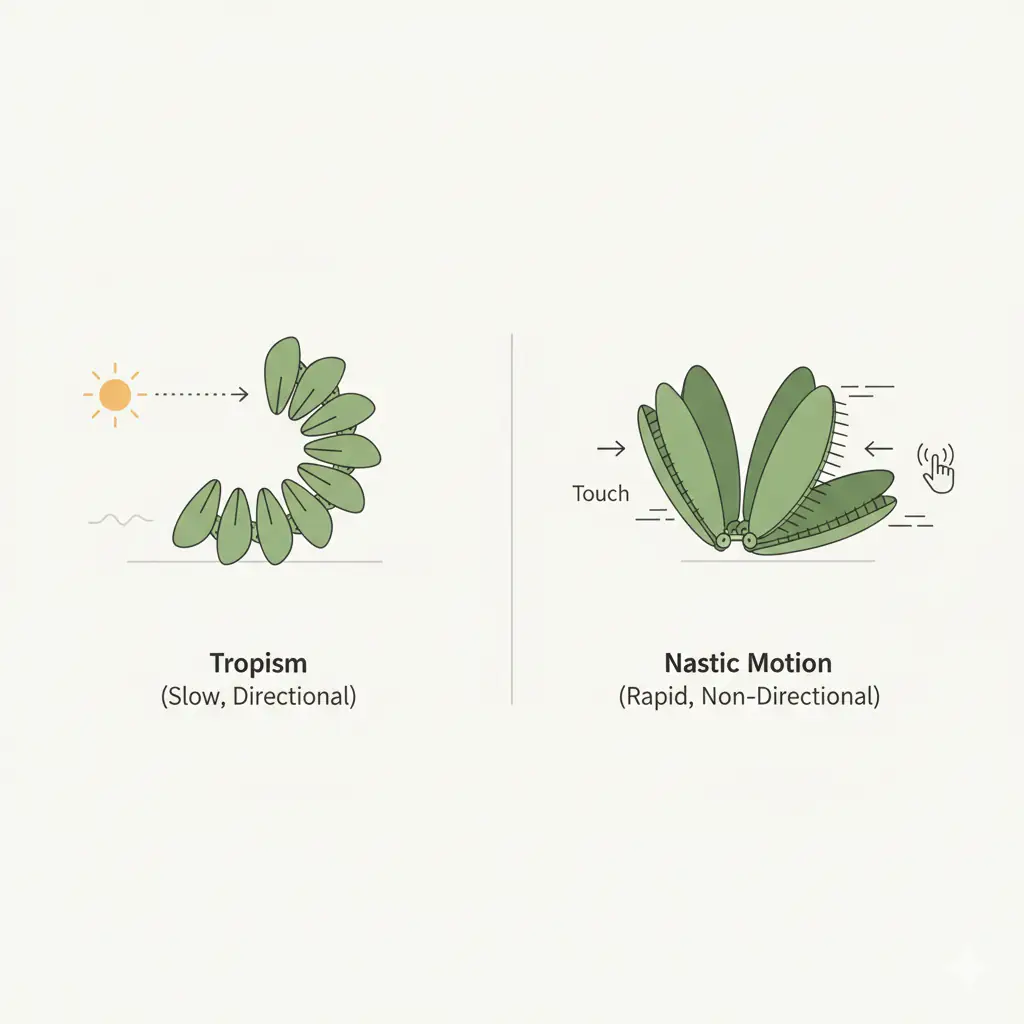

Soft robotic actuators, however, are made from compliant materials such as silicone, rubber, and flexible polymers. They mimic biological muscle structures, allowing for safer, gentler, and more adaptable movements.

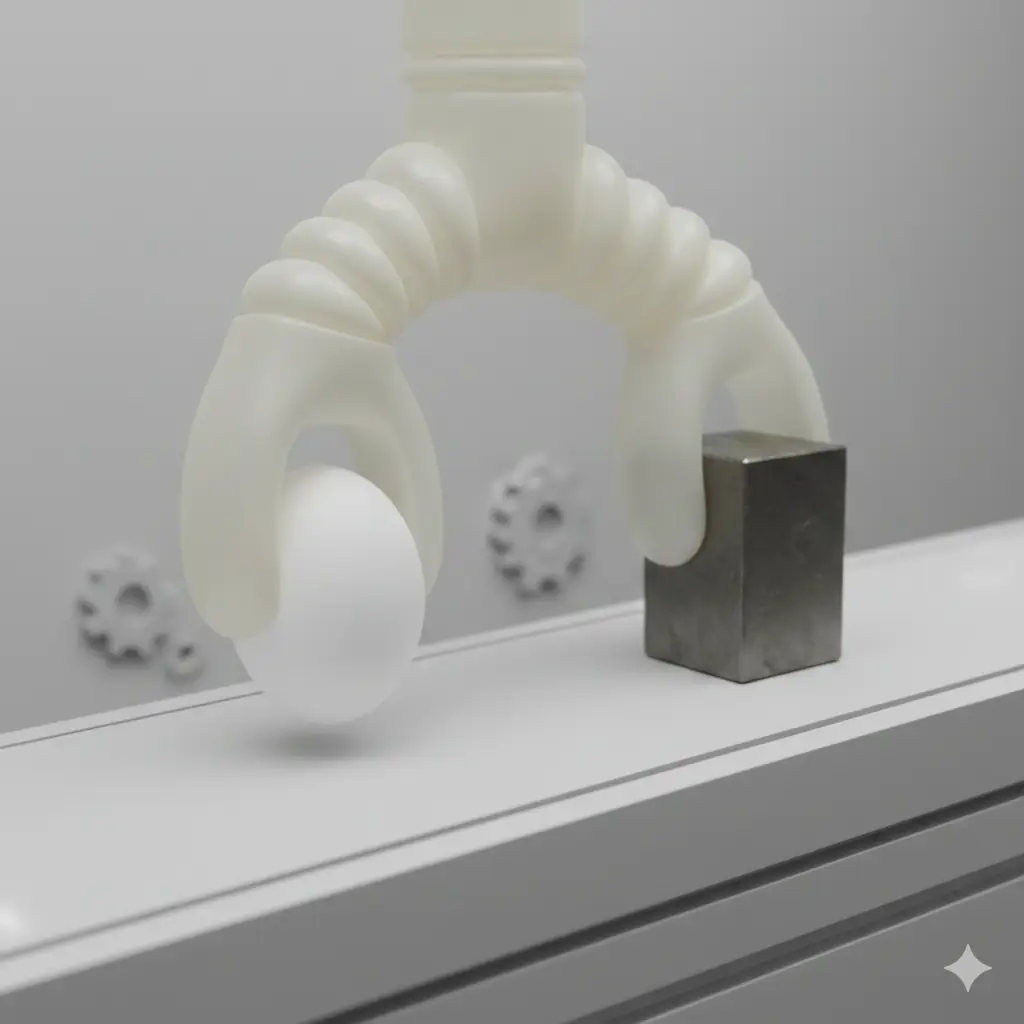

Instead of relying on complex mechanical linkages, they often use fluid pressure—pneumatics or hydraulics—to inflate and deform. This allows them to bend, twist, and grip with inherent compliance.

How Soft Actuators Work

Consider a simple, air-powered soft actuator. It consists of a chamber with patterned channels; when air is pumped in, the chamber expands and curls in a predictable direction.

This basic principle allows the actuator to gently conform to the shape of any object it touches. They can pick up a delicate raspberry with the same mechanism used to lift a metal cylinder.

Their compliance means they can absorb shock and distribute force evenly, which is critical when handling sensitive or oddly shaped items without causing damage.

Optimizing for Variable Product Lines

This is where soft robotics truly shines in the flexible manufacturing environment. Their inherent adaptability solves many long-standing automation challenges.

Key Advantages in Handling Variability

Traditional rigid grippers must be custom-machined for a specific part. If the product size changes, the gripper must be replaced, leading to expensive downtime.

Soft grippers and actuators offer intrinsic adaptability. A single soft gripper can handle a wide range of shapes and sizes—from a flat circuit board to a complex, curved casing—without any hardware changes.

They are also inherently safer for workers, as they lack the high-impact, crushing force of rigid components, making human-robot collaboration easier.

- Shape Conformity: Soft actuators naturally mold to irregular or varied geometry, unlike fixed mechanical jaws.

- Variable Force Control: They can be programmed to exert precise, gentle force, easily switching from handling fragile glass to heavy plastic.

- Reduced Tooling Costs: Manufacturers save significantly by not needing to design and purchase a new end-effector for every product variant.

- Faster Changeovers: Software adjustments to air pressure or control parameters replace time-consuming physical hardware changes.

Ultimately, this ability to adapt quickly and broadly is what defines a truly flexible production line.

A Look at Specific Applications

In electronics assembly, soft actuators can gently handle flexible printed circuit boards, ensuring fragile components aren’t stressed or cracked.

In the food industry, they are perfect for picking and packing delicate items like fruit and baked goods, reducing product damage dramatically compared to traditional suction cups or claws.

For consumer goods, the same robotic arm might switch from assembling a perfume bottle cap to packaging a shampoo dispenser just by adjusting the air pressure.

Technical Design & Future Outlook

The design of these actuators is constantly advancing, focusing on materials science and control systems. Researchers are developing smart materials that can change stiffness on command.

This means a gripper could be soft for the picking process and then momentarily stiffen up to ensure stable, secure transport. This capability adds another layer of dynamic flexibility.

| Actuator Type | Material Flexibility | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Pneumatic Bellows | High | General object gripping (variable shape) |

| Hydraulic Chambers | Medium-High | High-force, flexible manipulation |

| Shape Memory Alloys | Variable (Stiffens) | Precision positioning and latching |

Further innovation will focus on making the control of these systems simpler and more intuitive for factory operators, integrating them seamlessly with existing automation infrastructure.

Design Insight: The true elegance of soft robotics lies in using material properties to solve complexity. By making the hardware compliant, the need for intricate programming to avoid collisions or damage is significantly reduced, simplifying the overall system design.

The next generation of flexible manufacturing hinges on making this compliance a standard feature, not an exception.

Conclusion

The shift to flexible manufacturing is more than a trend; it’s an economic necessity driven by modern consumer behavior. Soft robotic actuators are proving to be the ideal ‘muscles’ for this new, adaptable production environment.

By offering intrinsic shape and force adaptability, they make rapid product variation not just possible, but efficient and economical. They are the quiet engine driving the factory of the future.

We can expect to see soft robotics move from niche applications to becoming a foundational element across all industries demanding high flexibility and gentle handling.