Unveiling the Power of Plant Movement

When we think of movement in nature, our minds often jump to animals—running, flying, or swimming. But plants, seemingly static, perform some of the most elegant and efficient motions on Earth.

These movements, driven by changes in cell pressure or differential growth, offer engineers a blueprint for creating a new generation of adaptable and compliant machines: soft robots.

Soft robotics is all about using flexible, elastic materials to build machines that can interact safely with the environment and people. What better inspiration than organisms that change their shape without any rigid joints?

The Three Plant Movement Prototypes

Engineers studying soft morphing focus mainly on three core types of plant movement. Each offers a unique mechanism for actuation—the process of initiating motion or control.

Mimicking these natural mechanisms allows us to design robotic components that can subtly and continuously change their form, much like a growing vine or a closing Venus flytrap.

1. Mimicking Tropisms: Directional Response

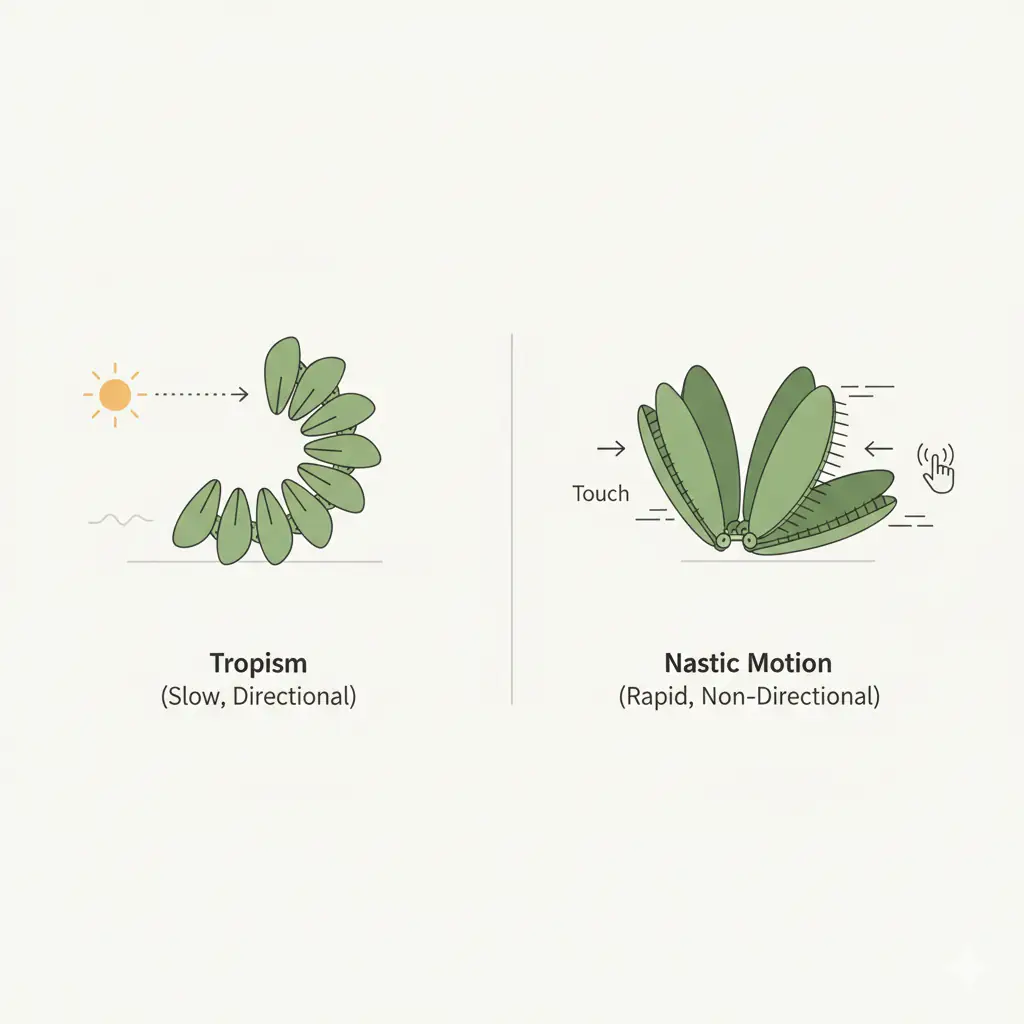

A tropism is a growth or turning movement in response to an external stimulus, where the direction of the movement is determined by the direction of the stimulus itself. Think of a sunflower tracking the sun across the sky.

Phototropism (response to light) and gravitropism (response to gravity) are the most studied examples. Plants achieve this by uneven cell elongation, often guided by hormones.

In soft robotics, we mimic this with materials that expand or contract asymmetrically when exposed to a specific cue, like heat or light. A light-sensitive polymer strip, for instance, could bend toward a light source.

This provides a simple, energy-efficient way for a robot to autonomously orient itself toward a desired condition or resource.

Micro-Case Example:

A research team developed a soft, cylindrical actuator coated in a black layer. When one side is heated with a laser, the material expands and bends in that direction, performing a precise thermotropism that can be used for steering a micro-robot.

2. Nastic Motion: Independent of Direction

Nastic movements are rapid, non-directional responses to a stimulus. Unlike tropisms, the movement’s direction is pre-determined by the plant’s structure, not the stimulus’s source.

The famous closing of the Venus flytrap or the rapid folding of a sensitive plant’s (Mimosa pudica) leaves when touched are classic examples of thigmonasty (response to touch).

These motions are usually powered by turgor pressure changes—the plant quickly shifts water volume between specialized motor cells. This results in incredibly fast, hinge-like actions.

In soft systems, this is translated into actuators that rapidly inflate or deflate chambers with air or liquid. This allows for quick grasping, opening, or closing actions, useful for sorting or gripping fragile objects.

It’s about high-speed shape change, moving from one stable state to another without the slow, continuous adjustment seen in tropisms.

3. Growth-Like Actuation: Irreversible Morphing

The third, and perhaps most complex, inspiration is growth itself. Plants achieve impressive feats of deployment—like a tightly folded leaf unfurling or a root forcing its way through soil.

This type of actuation is often irreversible, meaning the structure stays in its new shape. It mimics the fundamental biological process of a cell changing its size permanently.

Engineers achieve this growth-like morphing using techniques like additive manufacturing (3D printing) where new material is deposited to permanently extend a structure, or by using swelling hydrogels that expand and lock into a new configuration.

This is crucial for applications that require a robot to navigate a tight space and then stiffen or expand into a complex, load-bearing structure, such as anchoring a sensor in a deep crevice.

The Material Science Foundation

The success of soft morphing hinges on the materials used. They must be highly responsive to external cues and possess the right mechanical properties to ensure repeated, reliable motion.

Common materials include hydrogels, which change volume in response to $\text{pH}$ or temperature; shape memory polymers, which can be programmed to remember a second shape; and various elastomers (like silicone) embedded with active fibers or fluidic channels.

The key insight borrowed from plants is the use of composites. Plants achieve sophisticated bending because their tissues have different stiffnesses on opposite sides of the bending region—a principle directly applied in soft pneumatic actuators.

Future Applications and Innovations

The goal is not just to make devices that look like plants, but to capture the underlying principles of their efficiency, silence, and compliance. This technology holds promise across several fields.

- Minimal-Invasive Surgery: Deployable surgical tools that can navigate the body’s complex pathways and then expand or grasp precisely.

- Reconfigurable Structures: Architectural elements or camouflage systems that change shape in response to environmental conditions like light or heat.

- Search and Rescue: Robots that can grow and extend into rubble or wreckage to look for survivors without disturbing unstable environments.

Strong Insight:

The ultimate efficiency of plant-inspired robotics lies in distributed actuation. Instead of one large motor, the entire structure acts as the motor, leading to silent, gentle, and highly compliant movement.

Notes on Challenges and Outlook

While inspiring, plant-like actuation is not without its challenges. The response speed of some swelling polymers can be too slow for many robotic tasks, and controlling the precise degree of bending is often difficult due to material non-linearity.

However, ongoing research is improving the integration of smart sensors into these materials and developing faster-responding hydrogel and polymer blends. This is accelerating the transition from laboratory prototypes to practical applications.

The future of soft robotics is inherently green—not just in color, but in the bio-inspired efficiency and graceful movement of its natural mentors. We are learning to build machines that bend, grow, and respond with the silent, adaptive power of a sunflower or a root tip.

Leave a Reply